The Goal Of The Kremlin Is To Create Division Abroad

By GRACE BANFIELD

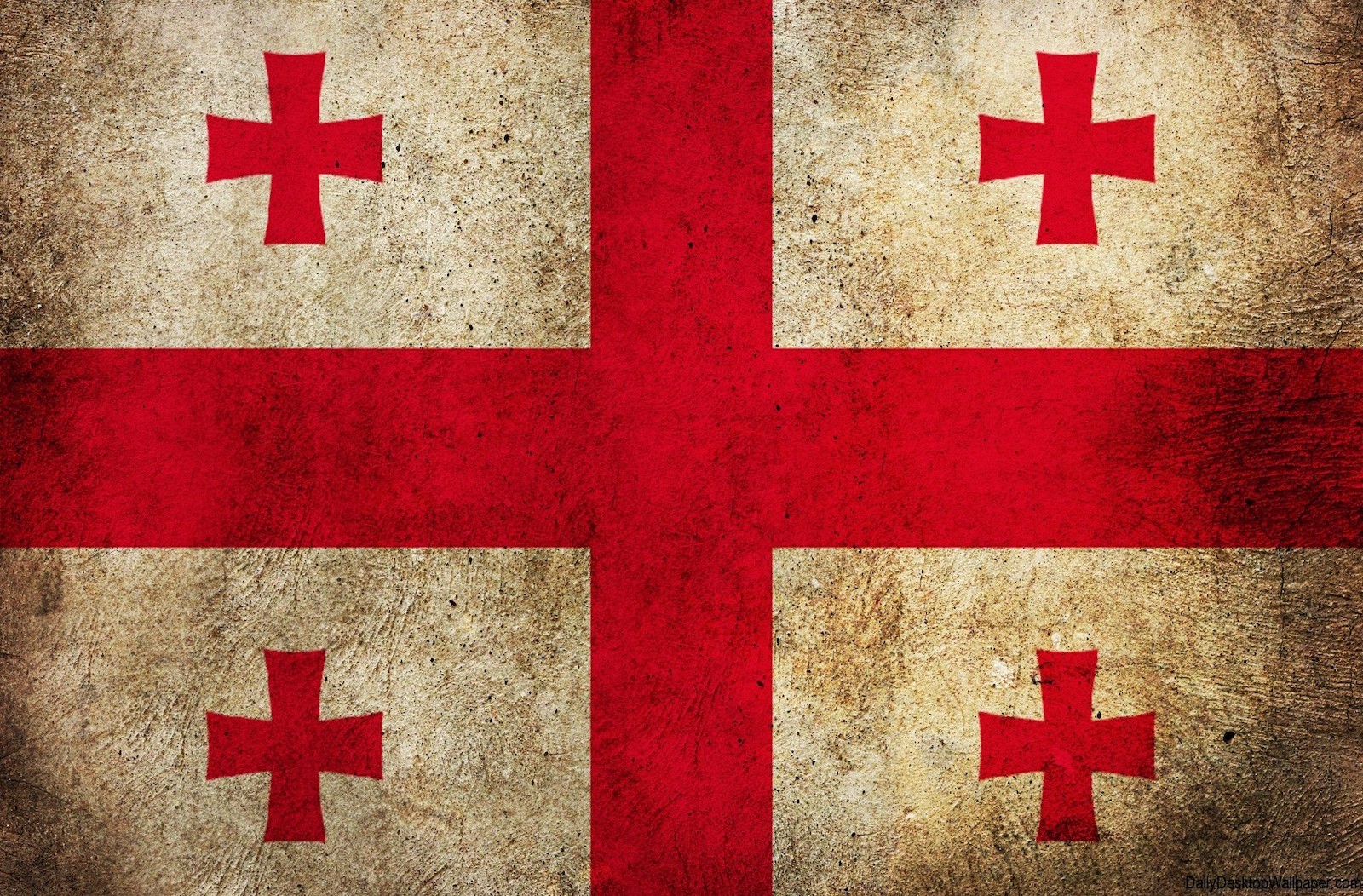

Mark Mullen was born in Dallas, Texas. He graduated from Wesleyan University in 1989 and later went on to be a Sloan fellow at London Business School. He has founded several non-profits, including GeoCapital, Orbeliani, and Radarami, in the Republic of Georgia, the former Soviet Republic at the intersection of Asia and Europe. Until President Shevardnadze resigned, Mullen was the director of the National Democratic Institute in Georgia. After the 2003 Rose Revolution, he started the Georgian chapter of Transparency International. He recently founded BeTheWave, a non-profit in the United States aimed at increasing voter turnout by leveraging social networks.

Can you give a brief summary of the Rose Revolution?

After the Soviet Union broke up in the 1990s, Georgia was one of the first republics to declare independence. Shevardnadze had been the foreign minister of the Soviet Union and realized that, as a non-Russian, there wasn’t much of a place for him there. In 1992 he returned to power in Georgia, at which point the country was in real tumult. He successfully pacified the country by giving out chunks of the economy and territory to various individuals who were allowed to profit from in exchange for maintaining order. From 1994 until 2000 there was a policy of peace through corruption. The stagnation that resulted from that corruption meant that by 2001 almost nobody believed Georgia could flourish under Shevardnadze.

All the real opposition to Shevardnadze was within his own party from young and western-educated people. Misha Saakashvili was the one who pushed the opposition farthest and fastest. His political party, affiliated media channels, and non-profit organizations created a sense of urgency involving all parts of society, especially young university students. They organized around an election that they knew, if it was fair, the opposition would win. Shevardnadze had almost no support at that point, so the incumbent government would be forced to either lose the election or falsify its results. The opposition was very well organized, using examples from Serbia and Slovakia. Above all they were very focused on peaceful means, knowing that any violence would favor the Shevardnadze regime who wanted—needed—any excuse to crackdown.

Was the revolution successful? Did the people get what they wanted for the most part?

Shevardnadze resigned, so it worked in that sense. The reason people were upset with Shevardnadze was corruption. Saakashvili, on the other hand, got rid of petty corruption largely through systems analysis, deregulation, and moving administrative processes online. The Saakashvili administration was also successful in getting rid of street crime. However, in the process, they took too much control over the criminal justice system. Police would take young people, arrest them, and force them to inform, which became another source of insecurity. People were afraid, and that fear was used politically by the government at times. There were essentially no checks on power. Also, there were more and more big, poorly-planned, poorly-executed vanity projects of senior officials that looked like corruption to the people.

Saakashvili was voted out in parliamentary elections in 2012, and a one-year transitional period followed when he left as president. Executive power was peacefully transferred, which is extremely rare in that area of the world. In that sense, the revolution was a success.

How did Russia interpret the Rose Revolution?

Russia has deep connections with Georgia. Georgia has great personal and symbolic meaning for the Russian people as a place of hospitality, freedom, and escape. It means a lot to them. The Kremlin believes Georgia should be a Russian colony.

Georgia was so corrupt under Shevardnadze and enough of it was occupied territory that it was never a major concern for Russia. Putin was focused on domestic power consolidation and only turned his attention to the revolution unfolding in Georgia when that goal was achieved.

Russia exerted control mainly through Georgian security services and continued to receive intel from many agents still floating around the country. It was the humiliation caused by the rounding up of these agents in 2006 that got Putin to plan an invasion of Georgia, which ended up happening in 2008. Putin guessed that the world would not go to war with Russia over Georgia, and he was right. Instead, Russia occupied South Ossetia and have used it as an instrument of instability and division as they have done in many other places.

What can the US learn from Georgia’s experience with Russia after the revolution?

When Shevardnadze was in power, the way that Russia tried to influence Georgia was very crude. Russia paid agents, and everybody knew who those agents were. During the 2008 invasion, Russia realized how little they were able to control international media conversations. They also started to build capacity both overtly and covertly within Georgia.

They gave up the old agents on payroll and moved to an extremely decentralized model—so decentralized that the people they were paying often did not know who was paying them. Russians started supporting some of the most corrupt and nationalistic people in the country. Georgia is small, so very little money went a long way. They’d find corrupt individuals—journalists or Orthodox clergy, for example—who actively pedaled falsehoods and conspiracies. They paid them and, in doing so, amplified their messages. The whole operation was very casual, and few knew it was actually the Kremlin paying them.

The goal was to spread rumors and conspiracies to persuade people that there was no real truth, enemies were all around, and that secret plans existed to undermine Georgian national sovereignty, traditions, or morality. The Kremlin actively undermined Georgia’s aspirations toward Western ideals of economic opportunity, democratic culture, and freedom. After 2010, you started hearing people say that the West was promoting homosexuality or other perceived moral wrongdoings. Much of that was engineered by the Kremlin.

The goal of the Kremlin is to create division abroad and unity domestically, and that is the lesson the US has to learn. They don’t care about taking and controlling territory. With Crimea and the Donbas, it is not that they want control of that territory. It is that they want to create a problem for Ukraine that prevents it from controlling its own borders in general. The Kremlin uses instability as an instrument, and the Kremlin has successfully done exactly that in the United States recently.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.4.4″ header_font=”|700|||||||” header_2_font=”|700|||||||” header_3_font=”|700|||||||” header_4_font=”|700|||||||” header_5_font=”|700|||||||” header_6_font=”|700|||||||” custom_margin=”||50px||false|false” custom_padding=”||20px||false|false” hover_enabled=”0″ border_style_all=”dotted” border_width_bottom=”2px” border_color_bottom=”#e4e4e4″ locked=”off”] [/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]